Something to Talk About

Everyone at one time or another has forgotten the name of that one guy they used to work with, or the restaurant that had that one chocolate dessert they loved. Now imagine not knowing the word at all, or not being able to physically say it.

That is similar to what happens to patients after experiencing some kind of brain trauma, whether through stroke, a car accident, a neurological disorder or a fall during which the person hits his or her head.

It is also something a group of neuroscientists, led by Nitin Tandon, M.D., the director of the epilepsy surgery program at Memorial Hermann Mischer Neuroscience Institute at the Texas Medical Center and associate professor in the Vivian L. Smith Department of Neurosurgery at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) McGovern Medical School, will examine.

“More than half a million people have had the effect of a stroke on language in their brain,” Tandon explained. “Half of those cannot speak well as a result, and nothing can be done right now.”

Epilepsy is similarly devastating to those affected, taking away a person’s independence and making it difficult to do things like have a job, he added. Those affected by this neurological disorder also often have difficulty remembering names of things and people, like what happens following a traumatic brain injury. Many of these patients with epilepsy are candidates for surgical procedures that target the area where the seizures originate.

“We aim to help them be seizure free, for them to live a normal life, be able to get married and have children,” Tandon said.

Recently, Tandon and his group were awarded a $1.8 million National Institutes of Health grant to explore new treatments for people who have speech problems following a stroke, traumatic brain injury or other neurological disorder.

Tandon’s team includes Joshua Breier, Ph.D., of UTHealth; Greg Hickok, Ph.D., of the University of California, Irvine; Robert Knight, M.D., of the University of California, Berkeley; and Xaq Pitkow, Ph.D., of Rice University.

They will be conducting a series of experiments over the course of five years on about 80 patients that will look at word production by people whose brain waves will be monitored through the use of intracranial electroencephalographic (icEEG) recordings.

Unlike being able to move or see, which are hardwired into brains the moment they develop, language is something that is acquired later, and typically set in stone in humans before eight years of age, Tandon said.

“These areas are hardwired, so when there is an injury, there isn’t another part of the brain that can do this, so that’s why people end up with a speech deficit,” he said. “This can happen because of a stroke or brain injury from a motor vehicle accident or hitting your head. There are lots of reasons, but the net result is often similar.”

Speech lives in the brain in multiple places, including on the left side of the brain in the inferior part of the frontal lobe, the posterior part of the temporal lobe and the inferior part of the parietal lobe.

The frontal lobe is a large section of the brain, and doctors refer to an area within this lobe linked to speech production as Broca’s area, named after Pierre Paul Broca. People who have damage in this area have difficulty speaking, and even with minor injury, the ability to string words together with the right grammar is diminished, Tandon said.

Another area in the same region, called Wernicke’s area, named for German neurologist Carl Wernicke, deals with the comprehension of language. For example, if there is a pen sitting on the desk, a person can look at it and know that it is a pen, but the brain is unable get that visual information to work with the speech area so a word can be spoken. Additionally, the patient can have a great deal of difficulty understanding spoken language.

The healthy brain functions in some ways just the same as muscles do when a person goes to the gym. When people work out, blood flows to that certain muscle. Similarly, when they use an area of their brains, blood supply increases in that area. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can measure the change in blood flow, showing doctors which part of the brain is active during the language process.

However, what MRIs can’t do is tell doctors how or in what order language is happening, because all of that activity is too rapid for the MRI to collect, Tandon said.

The electrodes, on the other hand, pick up the signals in the brain when a seizure occurs. Tandon expects the electrodes to also show how words are chosen and then strung together to make a sentence.

“The brain is an interesting structure, because when an injury occurs, brain cells and supporting cells die and you end up with a hole,” Tandon said. “When it fills with fluid and scar tissue, it no longer looks or works like the brain.”

As part of the study, Tandon and his team will gather icEEG recordings from patients with epilepsy by inserting electrodes into the areas of the brain where doctors suspect the epilepsy is originating, or close to them. He explains that if they knew where the epilepsy was in the brain, they could just target it with surgery.

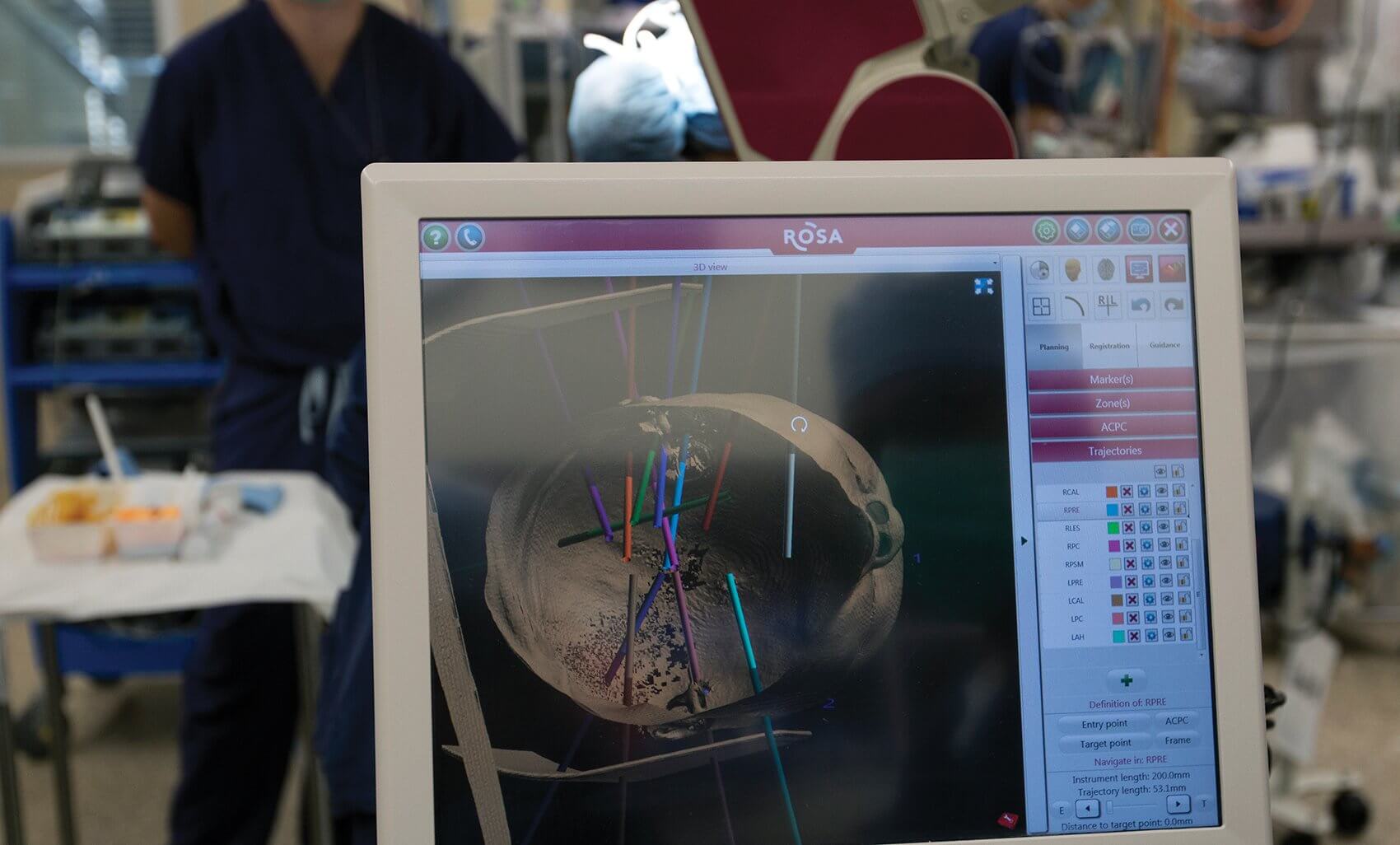

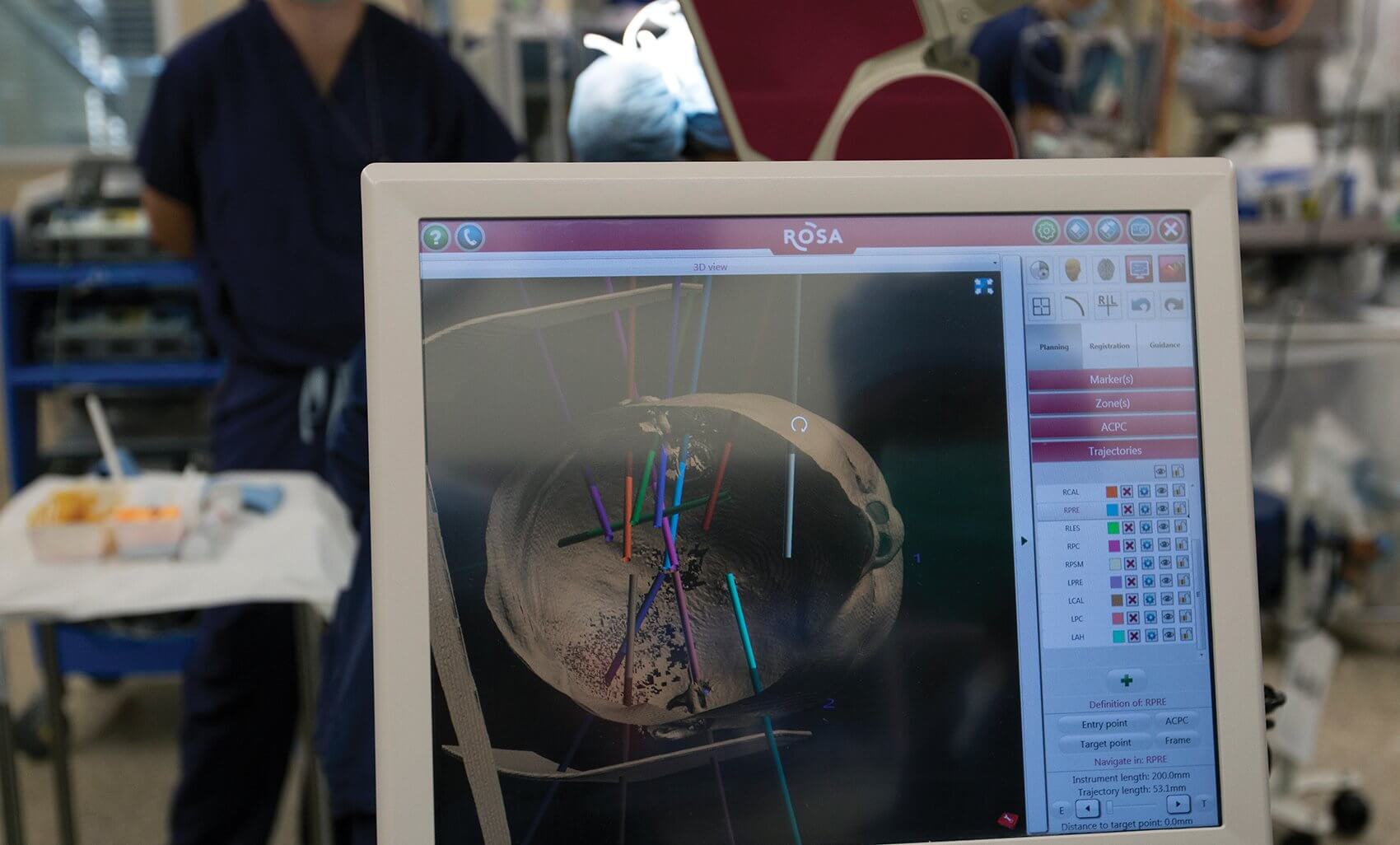

Following the surgery, which involves using a computerized robot to pinpoint the areas and angles that the electrodes will be inserted, patients are slowly taken off of their medication over the course of a week, so they will begin to have seizures.

While their brain activity is being monitored, they will engage in tasks and games on a computer that will have them name objects and perform other language functions. The doctors will use that information to construct a map of how language works in the areas where the icEEG recordings occur. The ultimate goal is to create a complete map of all the brain areas, Tandon said.

That research won’t be the end, though. Tandon said all of that informa- tion will take the form of maps of brain networks and equations that describe the interactions between the areas of the brain as the person thinks of words and forms sentences.

“The research will give us an understanding of how to take information from a normal brain area, connect it to another area and bypass an area that was damaged,” he said. “Where we eventually go with this research is creating a rehabilitation therapy that actually works, or a prosthetic device to integrate into their brain that can speak for them.”