Deciphering Zika

In 2015, Brazil witnessed a catastrophic increase in babies born with microcephaly, an incurable and detrimental condition in which head circumference is strikingly small and the brain fails to fully develop. Cases are historically rare and typically caused by genetic abnormalities, prenatal exposure to toxic substances or disease like herpes or rubella during pregnancy, but with nearly 3,000 cases reported in Brazil last year, the surge has prompted international concern as well as speculation that the worst is yet to come.

While scientists and public health officials do not yet have the data needed to conclusively determine what is causing the majority of microcephaly cases that are part of the epidemic, early evidence points to the Zika virus, which was first detected in the country around the same time and in the same regions as the microcephaly cases. Zika DNA has also been identified in the brain tissue of several stillborn babies with microcephaly.

“I believe there is more than enough evidence to tentatively link the virus to these microcephaly cases, but we’re working on scientific confirmation,” said Nikos Vasilakis, Ph.D., an associate professor in the department of pathology and a member of the Center for Biodefense and Emerging Infectious Diseases at The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (UTMB). At the request of the Brazilian government, Vasilakis and his colleague, Shannan Rossi, Ph.D., a research scientist in the department of pathology and at the Institute for Human Infections and Immunity at UTMB, traveled to the country in December to help set up diagnostic capabilities to verify the suspected link.

Utilizing reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays, Vasilakis and Rossi worked with members of FioCruz, a public health research institute based in Brazil, to detect viral RNA in blood samples as well as amniotic fluid. A majority of their trip was spent setting up local PCR capabilities in Salvador, a city located in the Bahia state of Brazil, which is one of the hubs of the epidemic.

“Having onsite diagnostics is essential when you are in the middle of an outbreak such as this,” Rossi explained. “Right now we don’t have a lot of answers, and that is very frustrating to the public and especially pregnant women in Brazil.”

Because viral RNA only tells part of the story, Vasilakis, Rossi and their team at UTMB are also developing a technique for detecting the presence of immunoglobulin M antibodies in cord blood. Once that test is refined, they’ll transfer the technology to Brazil for clinical use.

The chief epidemiological question concerns the link between the virus and these cases of microcephaly, but there are still countless other unknowns intrinsic to this outbreak. What is the window for a mosquito to spread the infection? Are you contagious before you are symptomatic? When are you no longer considered infected? How does the virus cross the placental barrier? What is the rate of replication? The virulence? If a correlation does exist, at what point in the pregnancy does an infection cause microcephaly in the fetus? Answers to these questions will help guide public health education efforts and infection control processes, as well as the development of potential vaccines or treatment options.

Until then, Brazilian authorities are proceeding with an abundance of caution, declaring a state of emergency and even advising women in infected regions to delay pregnancy until further notice. The CDC recently issued a travel warning to pregnant women planning to visit any of the infected areas, which include all of northwest Brazil as well as countries in Central and South America and the Caribbean.

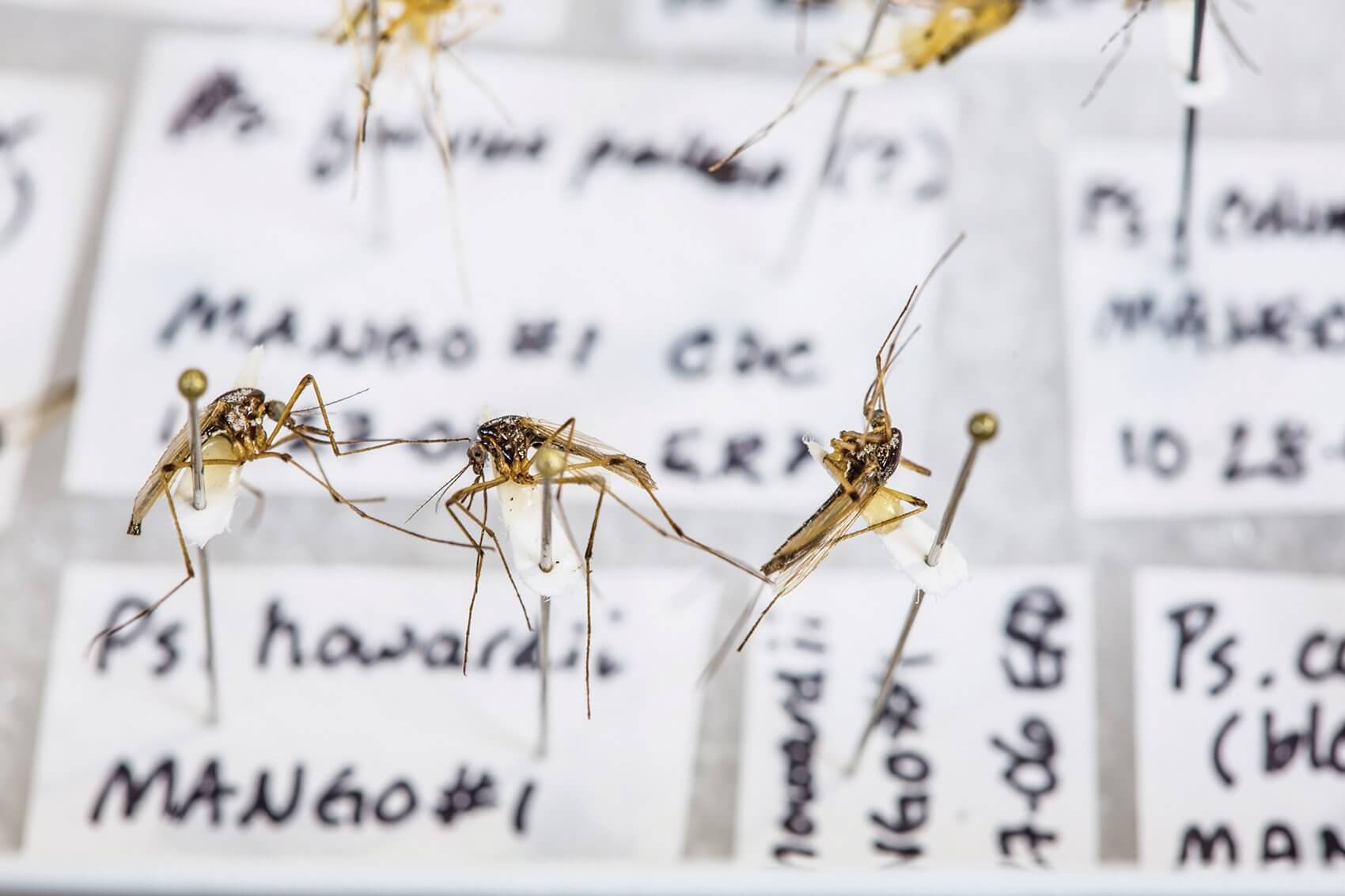

Because the vector for the disease— the Aedes mosquito species—is prevalent throughout tropical and subtropical parts of the world, it is likely that outbreaks will spread to even more countries via travelers. In fact, two cases have already been confirmed in Texas. While neither was acquired locally (both were tourists who acquired Zika while traveling), all it would take is one infected individual to be bitten by a mosquito, and for that mosquito to bite a different individual after incubation, then for another mosquito to bite that individual, and so on, to establish a transmission cycle.

“There is actually a big concern that this could become an issue in Texas because we have both the population density and the vectors capable of transmitting the disease,” said Vasilakis. “And with the jet age, it takes just a few hours for an individual to come all the way from Brazil to Texas. George Bush Intercontinental is a major hub, so that is a problem.”

Classified in the same family as dengue and West Nile, Zika was first discovered in Africa in 1947 and was, until now, considered a relatively mild arbovirus, causing only about a week’s worth of symptoms such as fever, rash, joint pain or conjunctivitis. Because there is currently no vaccine or treatment for the virus, individuals in infected countries have been asked to take standard precautions, including wearing long-sleeved shirts, utilizing screens on doors and windows, using mosquito repellents and clearing any standing water in broken flower pots or abandoned buckets, which are typically used as breeding grounds for the mosquitoes. Unfortunately, some of the hardest hit areas are also some of the poorest, where there is no air conditioning, few buildings with screens and very little access to repellents.

“What we’re seeing, I fear, is just the tip of the iceberg,” Rossi said. “As the rainy season starts to progress over the next few months, these cases are going to pick up because mosquitoes are going to be around to transmit the virus. And unless something drastic happens, we’re going to see another spike in microcephaly cases.”

It’s easy to read the data and nod along to the news about another mosquito-borne virus in tropical regions, but if the microcephaly cases are, in fact, fueled by Zika, this arbovirus could emerge as one of the most consequential in the world to date.

“It’s heartbreaking knowing so many babies are either going to die quickly or have a very substandard quality of life,” Rossi said. “Most of these babies are not going to walk, they’re not going to talk, and, with the most severe cases, they’re going to die soon after birth.”

Rossi retold a story about a woman at a clinic in Salvador who was happy and showing off her baby despite his microcephaly diagnosis. One of the social workers asked, “Why are you so happy?” and the woman replied, “They told me my baby was going to be dead when he was born. And he’s alive, he’s still with me.”

That’s going to be one of the big challenges moving forward, Rossi explained—helping these families navigate their future.

For now, UTMB is doing everything it can to gather information that will hopefully help control the disease. The Institute for Human Infections and Immunity is home to the Galveston National Laboratory (GNL), one of only two national biocontainment laboratories funded by the National Institutes of Health. Their state-of-the-art facilities include a CDC-inspected arthropod containment facility as well as the World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses (WRCERVA), which serves as the world’s primary virus reference center. Zoonotic viruses are identified, characterized and analyzed for the purpose of understanding their mechanisms and developing approaches for their control. The work Vasilakis and Rossi did in Brazil would not have been possible without the research gathered in these facilities.

“We need to continue to be vigilant and ready,” Rossi said. “We’re going to continue to stay on the bench and do everything we can here. We have a good core team at UTMB and we’re committed to getting these answers.”