How to Save a Life

In an oblong mass of over 1,000 acres, nestled between some of Houston’s most cherished landmarks—the museum district, the Houston Zoo and NRG stadium, to name a few—sits the beating heart of the city itself: the Texas Medical Center. Pulsing with clinical expertise, cutting-edge research and medical breakthroughs 24 hours a day, each and every day, it’s no surprise that the TMC is also home to some of the most robust organ and tissue transplantation centers in the nation, providing a rare second chance at life to those who need it most. Together, the centers offer the full spectrum of transplantation services, including heart, lung, liver, kidneys, pancreas and islet, tissue, nerves, multi-organ procedures, ventricular assist device (VAD) implantation, intestinal failure treatment and advanced organ failure management. While each program is now differentiated by its particular strengths, all were built upon a rich history of achievements in the field, including many of the nation’s firsts.

Leading the charge early on was Denton A. Cooley and the Texas Heart Institute (THI), successfully transplanting a human heart in 1968 and, just a year later, laying claim to the world’s first total artificial heart transplant. Now part of CHI St. Luke’s Health-Baylor St. Luke’s Medical Center, THI has been named among the nation’s best for cardiology and heart surgery for 25 consecutive years—a well-deserved title for a program that has implanted more than 1,000 VADs to date, more than any other program in the nation. Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center, in partnership with The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), pioneered the use of the anti-rejection medications cyclosporine and rapamycin, delivering revolutionary applications in immunosuppression therapies after transplantation. Texas Children’s Hospital, which has expanded into the largest pediatric heart transplant center in the country and one of the only pediatric lung transplant programs, performed the first successful heart transplant on an infant in 1984 and the first pediatric lung-kidney transplant in the nation. Meanwhile, the Houston Methodist J.C. Walter Jr. Transplant Center, starting from the first left ventricular assist device, achieved numerous firsts in heart, lung, liver, islet and multi-organ transplants while building a reputation as one of the largest and best organ failure management centers in the U.S.

To this day, the programs continue to grow in both volume and clinical outcomes. In fact, combined, they would create the largest, most successful transplant center in the country.

“Our outcomes in Houston are excellent,” said John Goss, M.D., professor of surgery and chief of the Division of Abdominal Transplantation at Baylor College of Medicine. Goss is also the JLH Foundation Endowed Chair in Transplant Surgery and medical director of transplant at Texas Children’s Hospital, as well as the director of liver transplantation at both St. Luke’s Medical Center and the Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center. “If you take the city of Chicago, or New York City, or LA, and you combine the survival of all of those programs and compare them to Houston, our numbers are much better,” he added.

It’s a claim that begs the question: why not unite? If the TMC is home to some of the country’s best, and if together their expertise would create a definitive transplantation superpower, why not collaborate to build one giant, comprehensive program?

“It’s an idea that’s certainly been proposed, but ultimately, I think we all agree it wouldn’t work very well,” explained J. Steve Bynon, M.D., program director for the Center for Abdominal Organ Transplantation & Regenerative Medicine at Memorial Hermann-TMC and UTHealth. Bynon was brought from the University of Alabama to Memorial Hermann-TMC four years ago to revamp their abdominal organ transplantation program, a move that has already resulted in an exponential increase in patients and above-national-average success rates. This, alongside the recently developed Center for Advanced Heart Failure at the Memorial Hermann Heart & Vascular Institute-TMC, quickly placed the institution among the heavy-hitters in the world of transplant programs.

“First, on a strictly logistical level, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services designates transplants based on individual hospitals, so from a reimbursement standpoint, combining our centers is an impossible proposition,” Bynon said. “Also, the competition is good. It forces all of us to perform at a much higher level, and I would hope that our resurrection of this program has facilitated that.”

Healthy competition aside, the sheer existence of a transplant program is often credited for breeding excellence within a hospital or health care system itself—another reason institutions would like to see their individual programs stay put.

“Transplantation is leading the way in quality care, and it has for some time,” Bynon said. “When you start to look at the principles of Accountable Care Organizations, those are all factors that successful transplantation programs have been implementing for years.”

Bynon explained that because transplantation is an extremely expensive endeavor for an organization, programs that hope to be successful from both a clinical and business standpoint must offer acutely specialized, high quality, efficient care, while producing excellent outcomes.

“Transplant programs raise the level of care across the board for every service line in a hospital. There isn’t a specialty that we don’t touch every day, and we’re demanding extremely specialized care that performs at a very high level. There’s no running up the bill and there’s no room for error,” he said.

That dedication to clinical excellence is ubiquitous in the transplant centers throughout the Texas Medical Center.

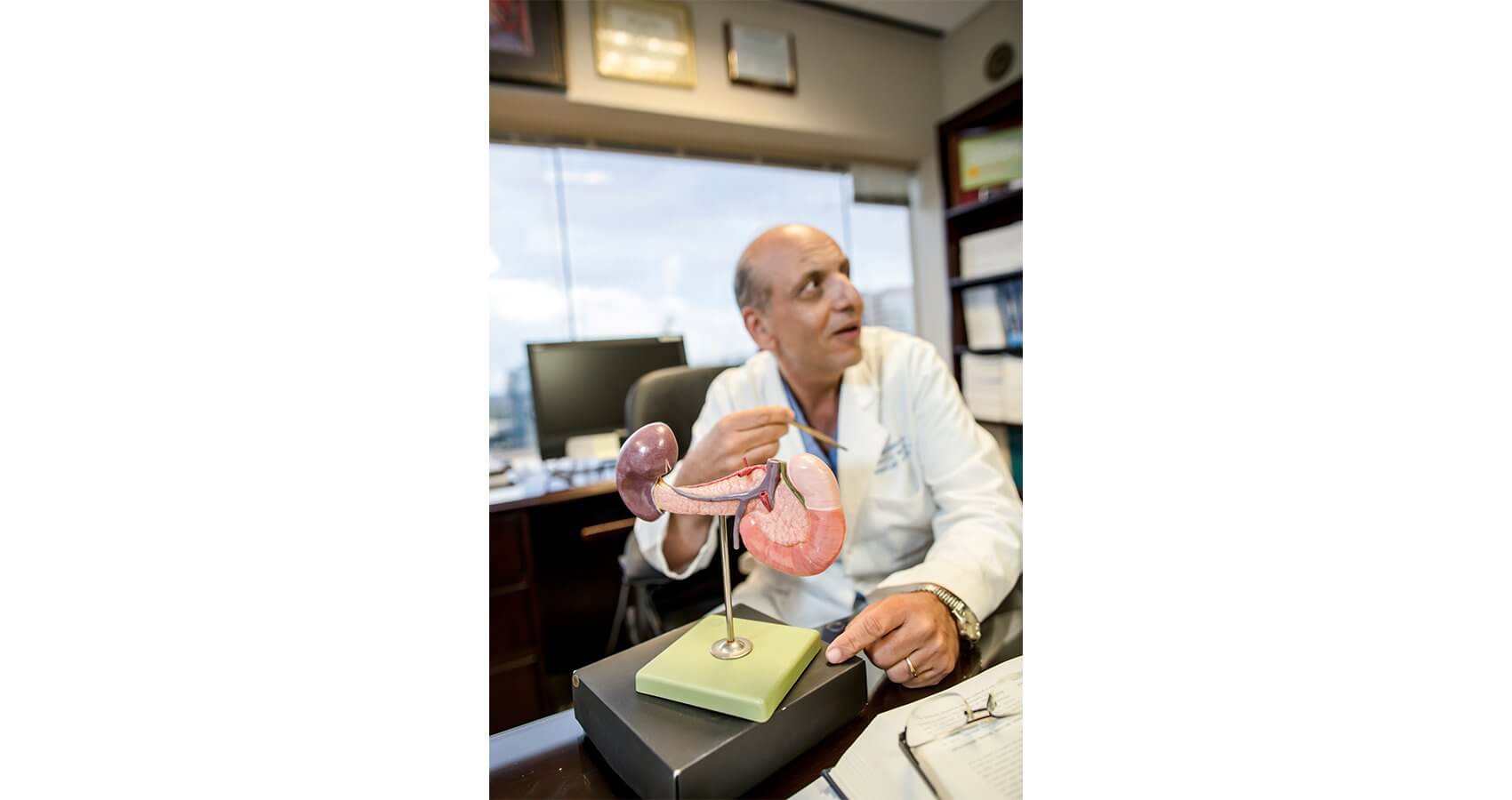

“Everything comes back to the patients and doing what is best for them,” said A. Osama Gaber, M.D., professor of surgery and director of the Houston Methodist J.C. Walter Jr. Transplant Center. “That’s really one of the things that sets our program apart. Methodist is not just a transplant program. Our center is organized in such a way that it is a large organ failure management system, committed to taking care of patients throughout all phases of care across the whole spectrum: inpatient, outpatient, during organ failure and post-transplant.”

Baylor College of Medicine physicians and surgeons support the transplant programs at Texas Children’s Hospital, Baylor St. Luke’s Medical Center, and the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, emphasizing the importance of a cohesive team and consistent standard of care for a program to be successful.

“We work to provide the same care at each of our hospitals,” Goss said. “We have one team of surgeons that covers our three facilities so that our standards are consistent—and our care is excellent.”

Excellent outcomes, of course, breed growth. In 2014, the lung transplant listings at Baylor St. Luke’s increased by 50 percent, their liver transplant listings increased by 54 percent and heart transplants increased by 48 percent. Texas Children’s Hospital, Memorial Hermann-TMC and Houston Methodist all witnessed substantial growth in their numbers as well.

As these programs continue to expand, caring for more and more patients while garnering national achievements and setting the bar for clinical excellence, the need to address other, non-clinical aspects of patient care becomes increasingly important. Nora’s Home, one of the Texas Medical Center’s newest member institutions, was created with this in mind.

A hospitality house designed to host and support transplant patients and their families, Nora’s Home includes private family suites, a chapel, community room and education center. It is named in memory of Gaber’s daughter, who tragically lost her life in an automobile accident at just seven years old; in honor of Nora’s spirit of compassion and generosity, Gaber and his wife donated her organs so she could save the lives of other children. Today, Nora’s Home is a welcoming place for out-of-towners who are awaiting their own lifesaving transplants, offering a community of support as well as lodging and transportation to and from the medical center. In addition to serving patients and their families in an often-overlooked capacity, Nora’s Home also provides an opportunity for the different member institutions to work in tandem, welcoming patients from the various programs throughout the TMC.

“We recognize that this is a time to really leverage the rich resources we have here in the medical center,” Gaber said. “We know that we get more when we have the conglomerates of the group rather than the individual pieces of it.”

Gaber sees this spirit of collaboration growing among the various programs, and not only in the non-clinical setting.

Just this past May, Houston Methodist partnered with The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and other TMC member institutions, including LifeGift, the designated organ procurement organization (OPO) for the Texas Medical Center, to perform a complex, first-of-its-kind multi-organ transplant involving a patient’s skull, scalp, kidney and pancreas—a procedure that would not have been possible without the breadth of expertise and cross-institutional collaboration available in the TMC.

“Already we are national leaders in our ability to perform complex, multi-organ procedures, and I think the more we act as one rather than our disparate parts, the more our patients will benefit,” Gaber said.

Gaber cited recent efforts to develop a TMC-based living donor collaborative as an excellent example of this kind of alliance.

Facilitated by LifeGift and the individual transplant centers, the living donor collaborative is a collective extension of a process that has been taking place within individual institutions for years: a patient needs a kidney, asks friends and family members until he or she finds a match, and the procedure is completed. All too often, however, patients are unable to find a living donor match within their social network, so they are put on the transplant list to wait until an organ from a deceased donor becomes available through the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), the vast, standardized network in charge of the allocation of organs throughout the United States. Patients in need of a transplant are matched with organs through the UNOS network based on numerous factors, including compatibility of blood type, tissue type, degree of immune system match, the size of the organ needed and the size of the organ donated, geographical location, medical urgency, and time spent on the waiting list. Some patients wait years for an organ match, and for most organs, this is the only option available.

Living donation is the exception to the rule. Bone marrow, blood vessels, stem cells, umbilical-cord blood and kidneys can all be donated by individuals during their lifetime. In extremely rare cases, a lobe from a lung or portions of the liver, pancreas, intestine or small bowel can also be donated by a person while he or she is still alive—and it can be done outside the UNOS system. Through the developing TMC living donor collaborative, member institutions are coming together to increase living donation possibilities through donor swaps. When a potential living donor and patient do not match, the transplant teams at the various programs arrange a series of exchanges between donors and recipients until each patient has a match.

“Say you have kidney disease and you have a donor that wants to donate to you, but the blood type doesn’t work out,” explained Goss. “We can put you in a pool with someone from Memorial Hermann or Methodist who is in a similar situation, and maybe the blood type of your donor works out from someone at Methodist and maybe the Methodist donor works out with someone from Memorial Hermann and then the Memorial Hermann donor works out with you. In the end you take all these pairs of living donors that don’t work out individually, but when you combine all the resources in the medical center and share amongst institutions, you’ve just saved three lives. It’s an excellent option to help our patients.”

Addressing the need for more organs doesn’t end there. Baylor, Methodist and Memorial Hermann-TMC are all engaged in cutting-edge research focused on alternatives to traditional organ donation and transplantation, including harnessing regenerative medicine, 3-D printing, stem cells and cellular structures to create new organs or fix those that are no longer working properly. Some researchers are even exploring xenotransplantation routes, which would modify animal organs such as pig livers, kidneys or hearts to be compatible with the human body. All of this is being performed alongside the institutions’ efforts in education and more traditional research focused on genomics, mechanical assist devices, immunotherapy, and breakthroughs in organ failure management techniques.

“I think one of the opportunities for growth in the medical center would be to team up across all the institutions to train fellows and collaborate in research. It would mean more people, more materials, and could really be the next step for all of our programs,” Goss said.

Until then, he explained, everything begins and ends with donations.

“None of this happens without the donor. In the end, you have to take care of people, and if you don’t have the organs, you can’t do that.”

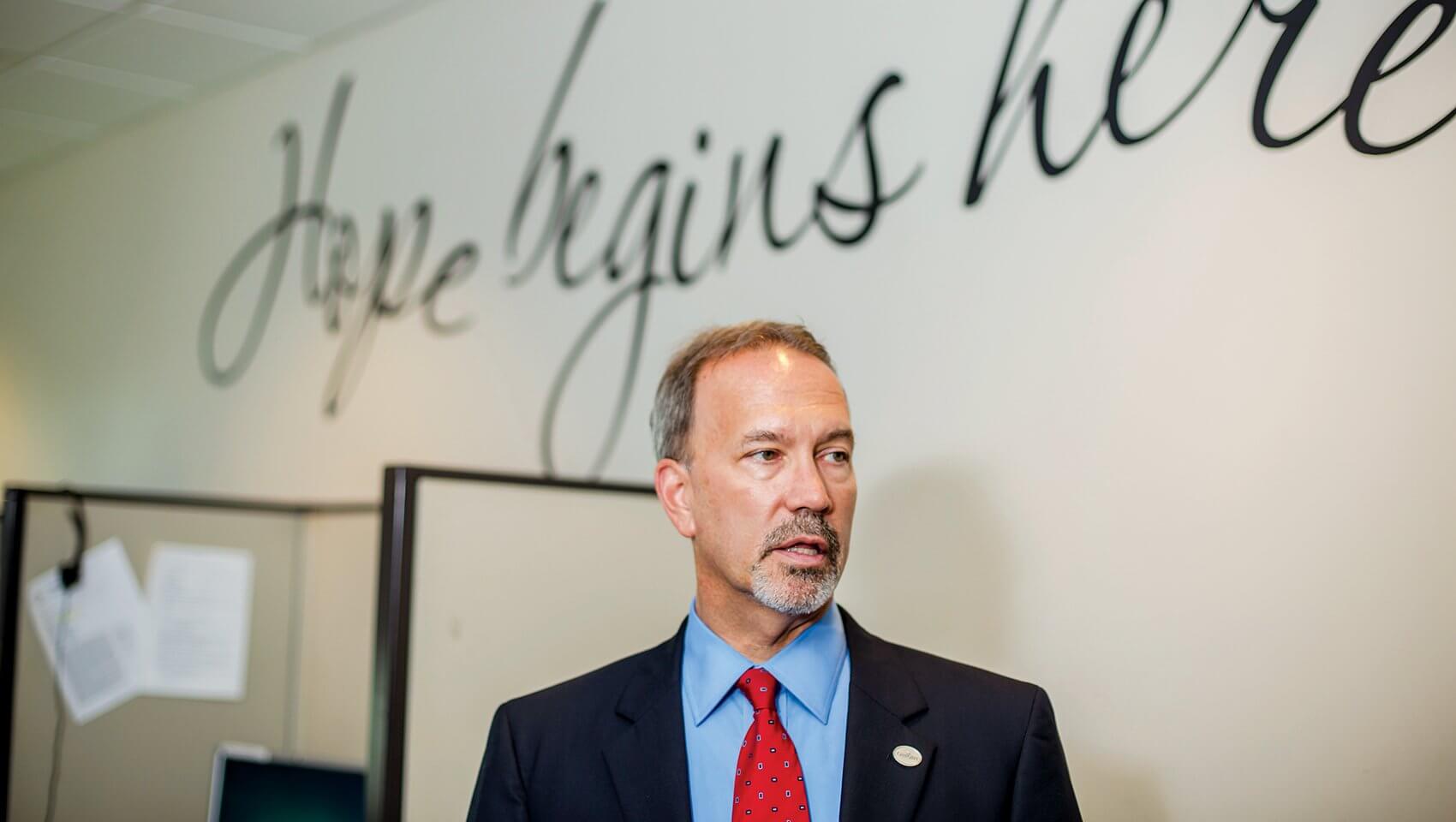

“It all happens because of a ‘yes,’” said Kevin Myer, president and CEO of LifeGift. In addition to being the OPO for Houston and its surrounding areas, the organization works diligently to increase the number of Texans entering the organ, eye and tissue donor database, known as Donate Life Texas. Through community outreach and education facilitated by LifeGift in collaboration with the Department of Public Safety and the state’s two other OPOs, the registry has increased from approximately 4 million Texans in 2012 to its current 7.7 million.

“This effort is in addition to working across all the TMC hospitals to coordinate organ, eye and tissue donation, usually with local TMC transplant centers. It’s exciting and reassuring to work with expert transplant programs, and we are confident that each donor’s gifts will have the best possible chance of saving lives when transplanted.

Still, it all comes down to a person, in the worst time of their life, saying ‘yes,’” Myer reiterated. “I think that’s one of the really important lessons about what we do when we ask people or their families to donate. In the midst of human tragedy, our job is to offer hope—hope for individuals on the receiving end, but also hope and value for the families of donors.”

That hope is something Karyn Trussell holds on to every day. Trussell’s son passed away three years ago, after his donated organs went on to save the lives of five different individuals.

“His best friend had been killed in a car crash not long before he passed away, and I remember he came home and said how glad he was that his family had donated his organs,” Trussell recalled. “So when it was time for me to make that decision, I didn’t hesitate. I knew that’s what he would have wanted me to do.”

“The donors are the true heroes in all of this,” said Bynon. “For the patients who get transplanted, I can tell you there’s not a day they don’t think about their donor and his or her family. They’ve truly helped somebody at a level that very few things can touch, and hopefully it helps them make some sense out of their tragedy.”

Organ donation is, after all, the act of giving life. It is fundamentally pure and selfless, a recognition of the interconnectedness between all of us. It is also, in a way, an act of preservation—and for the extraordinarily lucky, one of second chances.

“I’ve had so many blessings because of the gift of my heart,” said Randy Creech, a heart-transplant recipient who just this year celebrated the 25th anniversary of his surgery, a rare milestone for a heart transplant patient. At 40 years old, Creech was put on the transplant list and given one year to live after a viral infection in his cardiac muscle spurred aggressive congestive heart failure. On July 6, 1990, the call came that they’d found a match—a 19-year-old from Oklahoma named Aaron, who had passed away just hours before. Sitting next to Creech on the couch as he listened to the news was his own 19-year-old son.

“It was not an abstract thing,” Creech said. “Every day I marvel at the depth of that family’s love for other people, that they were willing to donate all the organs they could to help strangers. And to think that this same heart propelled Aaron through his life for 19 years and has now carried me for 25—it’s incredible. Thanks to his gift, I’ve been able to watch both my son and daughter graduate from college, get married, and have families of their own, and I still think about Aaron every day.”