10 Years Later: Remembering Hurricane Katrina

A decade ago, Aug. 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina made landfall in the city of New Orleans. Despite the city’s first-ever mandatory evacuation order, many thousands remained with plans to ride out the storm. As winds raged, the rain overwhelmed the city’s levees. Soon, close to 80 percent of New Orleans was under water and nearly 2,000 people perished in the storm.

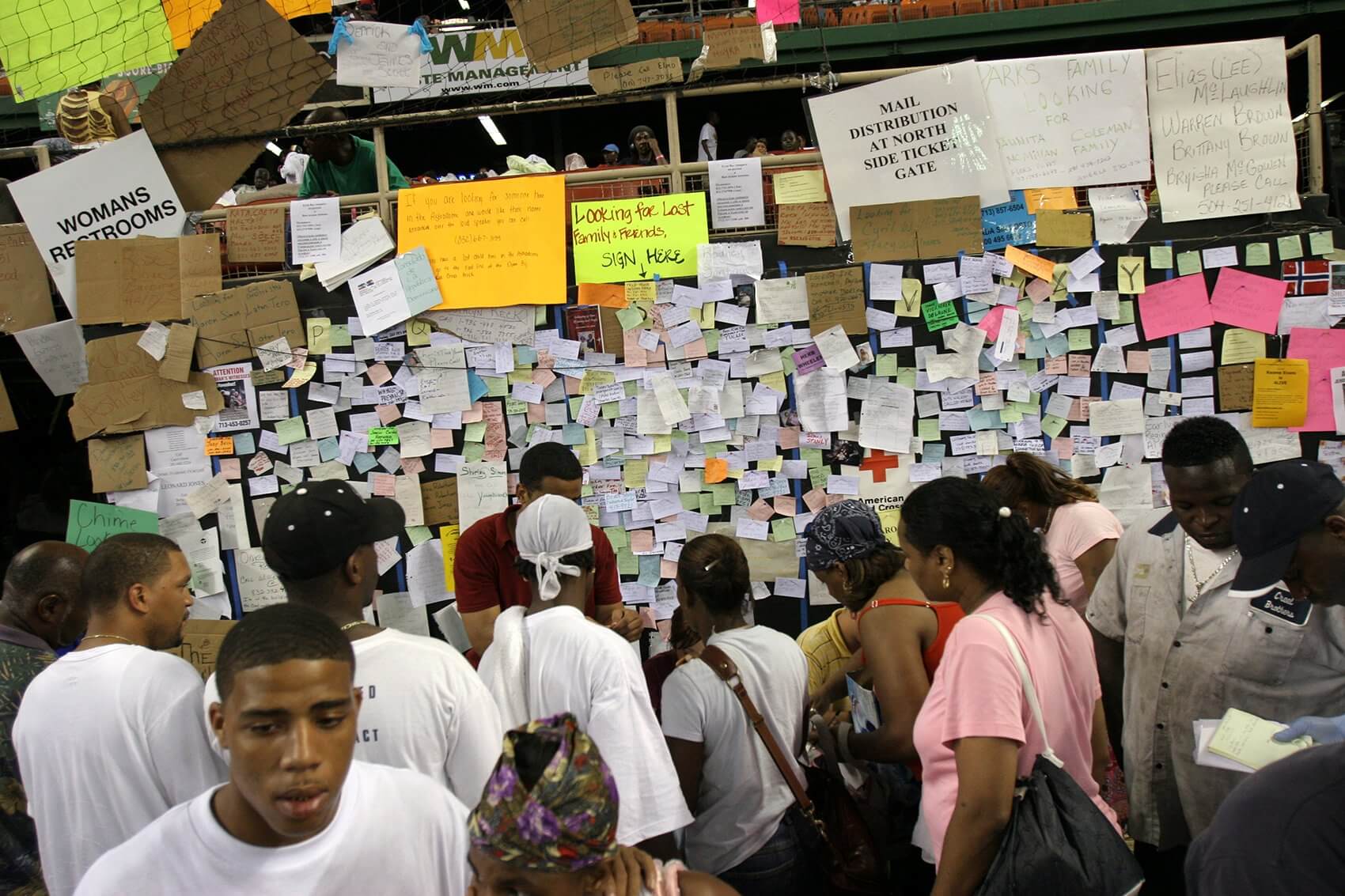

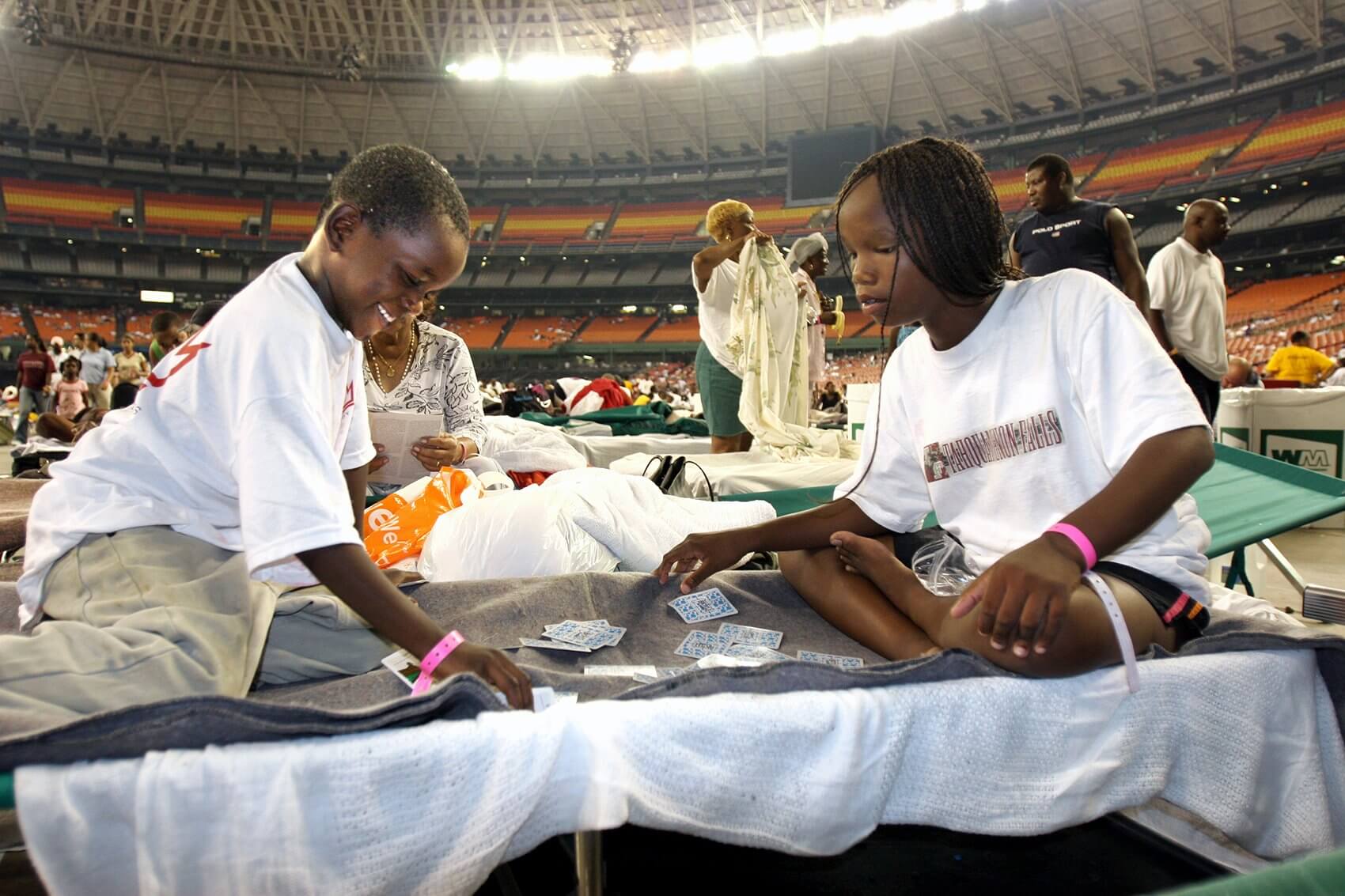

In Katrina’s wake, the city of Houston welcomed its eastern neighbors. By the time the rain and winds calmed, around 200,000 had evacuated to Houston, including about 25,000 from the New Orleans Superdome. Hospitals in the Texas Medical Center rallied together to provide care to the evacuees, from airlifting the sick and injured via Memorial Hermann Life Flight aircraft, to treating thousands in the Astrodome and the George R. Brown Convention Center. Below, five TMC members recall the events of 10 years ago and what it has meant for the Texas Medical Center and the city of Houston.

George V. Masi

Then: Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, Harris Health System

Now: President and chief executive officer, Harris Health System

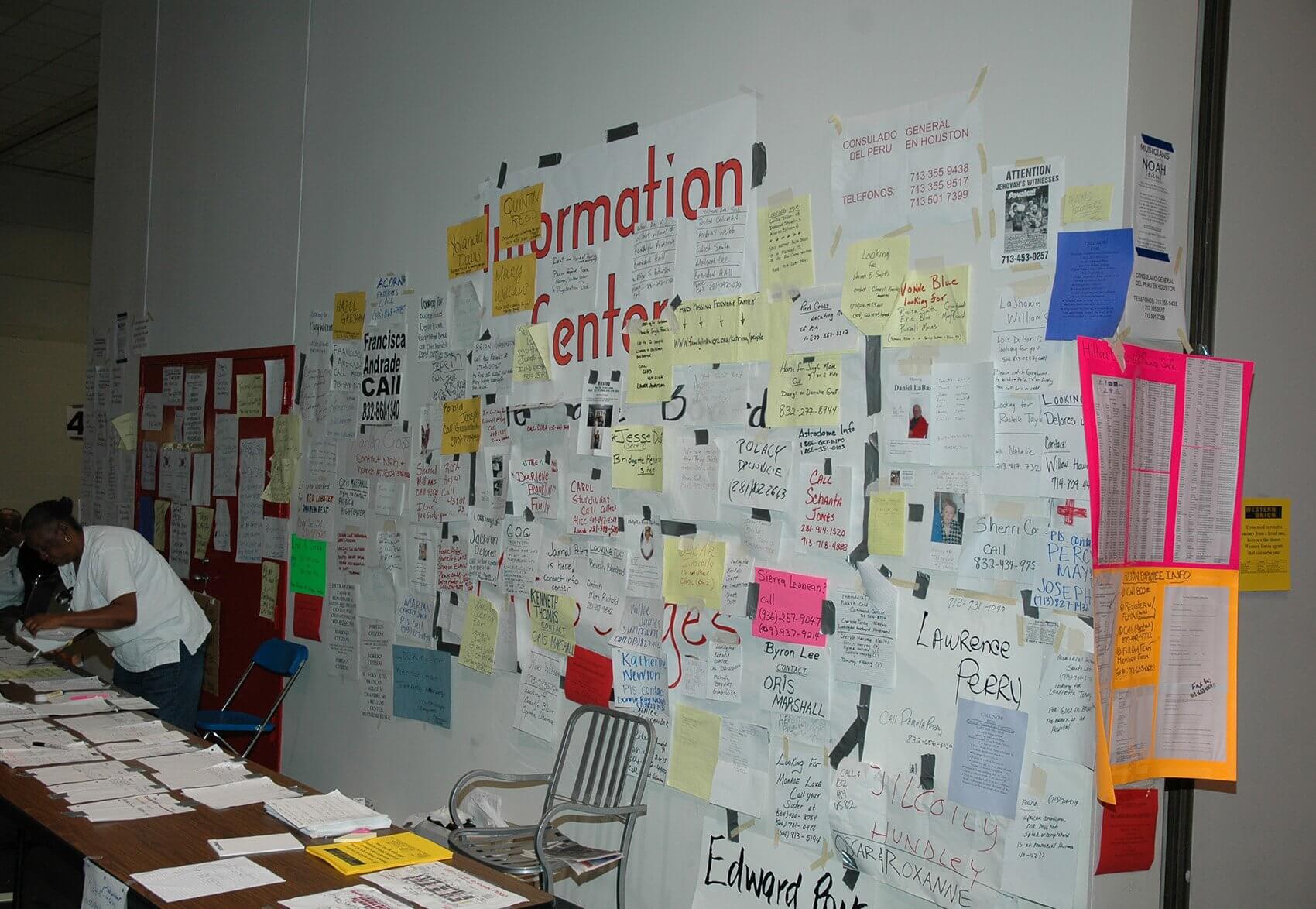

The afternoon of the 30th I think it was, we got a call to report to the emergency management center for Harris County. Then-county Judge, Judge [Robert] Eckels, had summoned us to the emergency management center at the direction of the Governor. The County judge specified that Harris County Hospital District [now known as Harris Health System] would have the role of responding to what came to be known as the ‘dome-to-dome’ relief for individuals stranded in the Superdome. As the meeting adjourned, we were convoyed over to the Astrodome complex. The first bus arrived early the next morning. Keep in mind, this was after these people had been in the Superdome for days, so we didn’t know what to expect. When we got to the complex, the building that had been designated for medical support, coincidentally contractors were taking down booths and barriers as part of a trade show that had just happened. We were told that we had access to the contractors—that they would be available to us to do anything we needed to do to modify the complex to accommodate the medical needs. We had a piece of chalk, the contractors gathered around and we started to draw out what this complex should look like. The receiving area, the triage area, emergency medicine, x-ray, pharmacy, laboratory. What the contractors did with that chalk sketch on the floor is that they began to re-assemble all of the piping and the drapes that had hours before been the trade show and they now became a hospital in this 100,000-square-foot complex.

We then began to strip out equipment and supplies from Ben Taub and LBJ Hospitals: beds, pillows, blankets, IV solutions, sutures and all the things that you would need for emergency management. We began to set that up and early in the morning, about 3 a.m., the first buses started to arrive. What became quickly apparent was that there were a lot of sick people coming in on these buses. As the buses came through the gates, we had a doctor or a nurse get on the bus and do some ‘battlefield triage,’ asking questions like, ‘How many people on this bus feel as though they have a temperature?’ ‘How many of you have diseases or medical conditions that pre-date your being in the Superdome?’ A lot of these patients had been without medications for days.

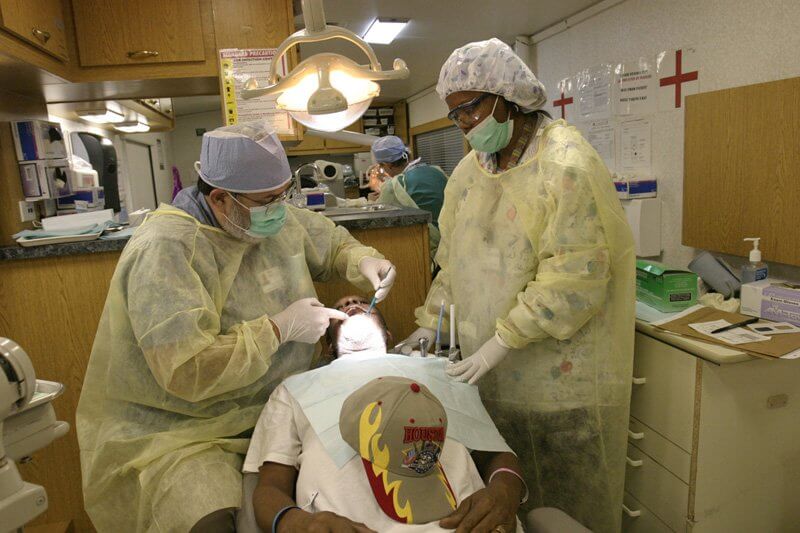

The first stop the bus made once it was in the compound was to the medical complex. Those patients disembarked from the bus and they were met by doctors and nurses and ushered into the medical complex where they were offered a shower, dry clothes, and hot food. The bus then went on to the Astrodome where the healthy individuals got off and had the same treatment—hot shower, clothes and food. The operation itself went on for over two weeks—24 hours a day, seven days a week. We saw and treated thousands of patients from everything from kidney disease and kidney failure to heart disease. A lot of individuals lost their eye glasses in the flood and couldn’t see. We opened up our own pharmacy where we were writing prescriptions for patients and filling them on the spot.

When all was said and done and we tallied up the numbers, there were thousands of patients that we saw and treated, thousands of prescriptions were written, hundreds of patients that were transferred from our medical facility to other facilities in the Texas Medical center for renal dialysis, some had surgeries, some had heart attacks and they went into the ICU and so forth. All in all, it was just a spectacular relief effort and we were able to help a lot of people. As tragic as that whole event was, for those of us who were on the receiving end, it was very gratifying and uplifting.

Tom Flanagan

Then: Administrative director of emergency services, Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center

Now: Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center

The first person we airlifted out of New Orleans was a transplant patient. That was Sunday afternoon. Monday afternoon, after Katrina had made landfall, I had gotten a call from a physician who was pretty emotional, trying to get a 14-year-old out of Charity in New Orleans who had been involved in a horrible motor vehicle collision. They needed to airlift him out. I sent a Life Flight aircraft to New Orleans and they landed at the Dome over there. The child was put in a boat and motored up to the dome and they got him to the pad. We airlifted him back.

That week, we repackaged our flight program daily responsibilities. At that time we were flying four aircraft. I took two of the helicopters and we flipped the pilot and the medical crew schedules with the mechanics. When the mechanics were done with their daily maintenance, the new crews would come in at one or two in the morning, they would load on the aircraft and fly from Houston to Baton Rouge. Once daylight came, they would fly to New Orleans and shuttle evacuees or critical patients over to Baton Rouge where they would either be put on the fixed wing or they would be put on the ground ambulance and be brought to Memorial Hermann-TMC in Houston. They’d do that all day long until nighttime. When dusk fell, because there were no lights or power, the helicopters would come back to Houston and we would change out crews, the mechanics would do the maintenance and then at 2 o’clock the next morning they would head back and repeat the same thing.

We set up a command center here at our TMC campus, and we were the bed control for all of our system hospitals, as well as the TMC campus. We would direct patients, so once they landed at Ellington, we could distribute them to the appropriate hospitals.

As you look back over the last 10 years, a lot of good things came out of all that. We’ve taken all the things we’ve learned, put them into practice, and then we drill every year. Drill, drill, drill to make sure everyone is current, what the expectations are. Houston has always been a city that, when there’s any type of disaster, natural disaster or other, the city really does pull together and support one another because it’s all about human life. That’s what we’re really here for. We come together as one and not separate entities and everyone works well together.

Claire Bassett

Now: Vice president of communications & community outreach, Baylor College of Medicine

Then: Vice president of public affairs

I got a call from Ken Mattox, the chief of staff at Ben Taub, because he had been notified that the county was going to open up the Astrodome to house people who were evacuated from Katrina. Obviously they were going to need medical care. What we did at Baylor was we sent out a call for physicians to all of our faculty, and then also looked at how residents and medical students could provide support on site. We set up a system where people could contact my office via email or phone and say, ‘I’m a cardiologist, I’m available Tuesday from 4 to 8 p.m.’ It really was a great community response effort.

Once the medical care got established, we began the process of trying to move the entire Tulane Medical School to Baylor. That became the bigger aspect of our response to Hurricane Katrina. We hosted the Tulane Medical School for the entire academic year. The schools are about the same size and their facilities had been so badly damaged that there was no way they could provide a medical education experience to their students. The first- and second-year students did all of their classes at Baylor, either taught by the Tulane faculty or supplemented by Baylor faculty. The third- and fourth-year students, who were doing clinical rotations, were split between Baylor, UT-Houston, UT-Galveston and Texas A&M to do their clinical rotations. I feel like had we not taken Tulane in, the Tulane Medical school could have been in jeopardy of disappearing. All of the fourth-year medical students were able to graduate on time, and they actually were able to hold graduation back in New Orleans. Everyone stayed right on track with their medical education and didn’t miss a beat.

It certainly showed that this is a very welcoming community, but I think more importantly, it showed that there is a really high value placed on collaboration in this city. Regardless of what your work affiliation might be, in times of crisis everybody puts everything behind them and looks for how to solve a problem that’s a really critical, devastating problem. That’s what showed the strength of the city.

Elda Ramirez, Ph.D.

Then: Assistant professor of clinical nursing, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth) School of Nursing

Now: Professor of nursing, Department of Acute and Continuing Care, UTHealth School of Nursing

I got a call: ‘We’re mobilizing to the George R. Brown. We’re setting up camp for anyone who is coming in.’ They told me where to go and I started calling my students and faculty. The entire school of nursing was involved, all of the faculty were involved and they brought all of their specialties. We walked into George R. Brown and they asked what we needed—they already had curtained off areas. People just started showing up from everywhere and they were wondering when the first load of people would be here. I said probably by eight or nine o’clock tonight.

We would make a phone call to the medical director at Memorial Hermann in the ER at that time. I would call and say, ‘We need a crash cart.’ And he’d say, ‘OK, give me a minute.’ He would make some calls and the next thing you know, a crash cart was on its way. One night I had a group of people who had special needs, and it was 11 o’clock and night and my husband was in charge of the unit that night—he is also a nurse. I called him up and I said, ‘They are bringing in a busload of special needs patients.’ He said, ‘Call more people, because I need more people.’ So then more people showed up. The volunteer part was just beautiful, I mean thousands of people just showed up, nurses and other providers. They mobilized and everything we needed was brought to us. I was the director of nursing at the George R. Brown and I had a charge nurse all day and a charge nurse all night, I had an entire pediatric area, I had a National Guard team, and they created an area with a tent that was just for psychiatric patients who had PTSD. Too much had happened around them so they built a quiet place for them.

The National Guard also created a fast-track area for people who needed immunizations or quick evaluations. We had a company who brought in x-ray equipment, we had an eyeglass company for people who need eyeglasses. We had Walgreens come in and set up a station. We had an entire makeshift town and it was fully functional. We had ambulances from all over the country lined up outside of the George R. Brown waiting for the triage. If they had a swollen hand or chest pain—bam! It was on. To me it was like a symphony. Everyone was working together all at once. Nurses from all walks of life, physicians from all walks of life, administrators, hospital systems—all working together.

Kim Holt

Then: Nurse Manager, Texas Children’s Hospital EC Rapid Treatment Area

Now: Nurse Manager, Ambulatory Infusion Center and Float Pool

Some of our ER department went down on the first two days to help set up what we ended up calling the Arena Clinic. On day three, I was brought in because they felt there was a need for a nurse leader to manage the operations of the clinic, the staffing coordination and working with the county on the efforts to make sure there was staff available for the clinics. From that point forward, I stepped in and assessed the situation: What were the needs, because it was still a little chaotic with the numbers that were coming in. There was no organization to it initially, we were trying to get through the large volume at that point. I stepped in and identified what kind of operation changes needed to be made to make this run as smoothly as possible. My goal was to set it up like we would do in a fast-track ER setting. I created a charge nurse role for the clinic, and TCH EC provided that person on 12 hour shifts. The charge nurse and I coordinated the staffing and all the miscellaneous things that came up. Tracking certain diagnoses that were coming in, for example we had an outbreak of the norovirus. For pediatrics, we didn’t see too many injuries or trauma—outside of psychological trauma. There was a lot of that. I reported out to executives every day on the volume we were seeing. I worked until the day we ramped down our operation when we saw the volume decrease to a level they felt was manageable by the hospitals in the medical center. We came up with an exit strategy and then implemented that on Sept. 11.

Ten years—it does not seem like it’s been that long. I still vividly remember a large part of my experience at the arena. It is still the highlight of my career and the most rewarding. The looks on those children’s faces when they came through and some of the stories they told will live with me for the rest of my life. Prior to Katrina I would not be sure if we were prepared as a city, but without a doubt, I 100 percent have no hesitation to say Houston is prepared. We have been there, we have done it. It was very impactful when you think about the volume we saw come through there—nearly 2,500 pediatric patients. That could have easily overwhelmed the health care system in Houston. This was done by volunteers. These were nurses and doctors working their normal, every day jobs and going down there to volunteer their time. It’s really quite amazing.