Danger at the Heart of Pregnancy

Imagine waking up in the middle of the night gasping for breath. That’s what happened to Diane Russo night after night during her last 12 weeks of pregnancy.

During her third and final pregnancy, Russo discovered that if she sat up, the problem went away. But after it kept happening repeatedly, she talked to her OB-GYN, who, told her it was because she was carrying a big baby, just as her previous babies had been.

When her condition worsened, she finally had an echocardiogram, which revealed blood in her lungs. Her doctor had her rushed immediately to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at CHI St. Luke’s Health-Baylor St. Luke’s Medical Center. Russo then had a Swan-Ganz pulmonary catheter inserted to monitor the heart’s function and blood flow.

Due to this pulmonary complication, Russo’s baby was induced two weeks early—only two days after her own hospitalization—on June 10, 1998, weighing 9 pounds 2 ounces. Now that her son was born, all she wanted to do was hold him as she fought for her life.

Her ejection fraction, the fraction of outbound blood pumped from the heart with each heartbeat, was as low as 11-12 percent when she gave birth.

According to Indaranee Rajapreyar M.D., cardiovascular disease specialist with the Center for Advanced Heart Failure at the Memorial Hermann Heart & Vascular Institute-Texas Medical Center (TMC)/UTHealth, the norm for most healthy people is between 55 and 65 percent. It was at this time Russo learned that if she ever got pregnant again, she would die.

Russo recalls how rough those first few days of her youngest son’s life were. Due to being jaundiced, he was sent to Texas Children’s Hospital while she stayed in the ICU at Baylor St. Luke’s Medical Center.

After 21 days, Russo was finally released from the hospital with her ejection fraction measuring at 19 percent. Over the years, it eventually raised. Russo, however, was never the same and had to return to the cardiologist for routine visits every six months for the first five years after the birth of her son, then once a year from then on.

Fast-forward 13 years. In late 2011, at a routine cardiologist visit, Russo’s doctor gave her some news. “It’s time,” were the words Russo remembers her doctor telling her, meaning it was time to get on the heart transplant list. By March of 2012, Russo recalls feeling “winded and sluggish.”

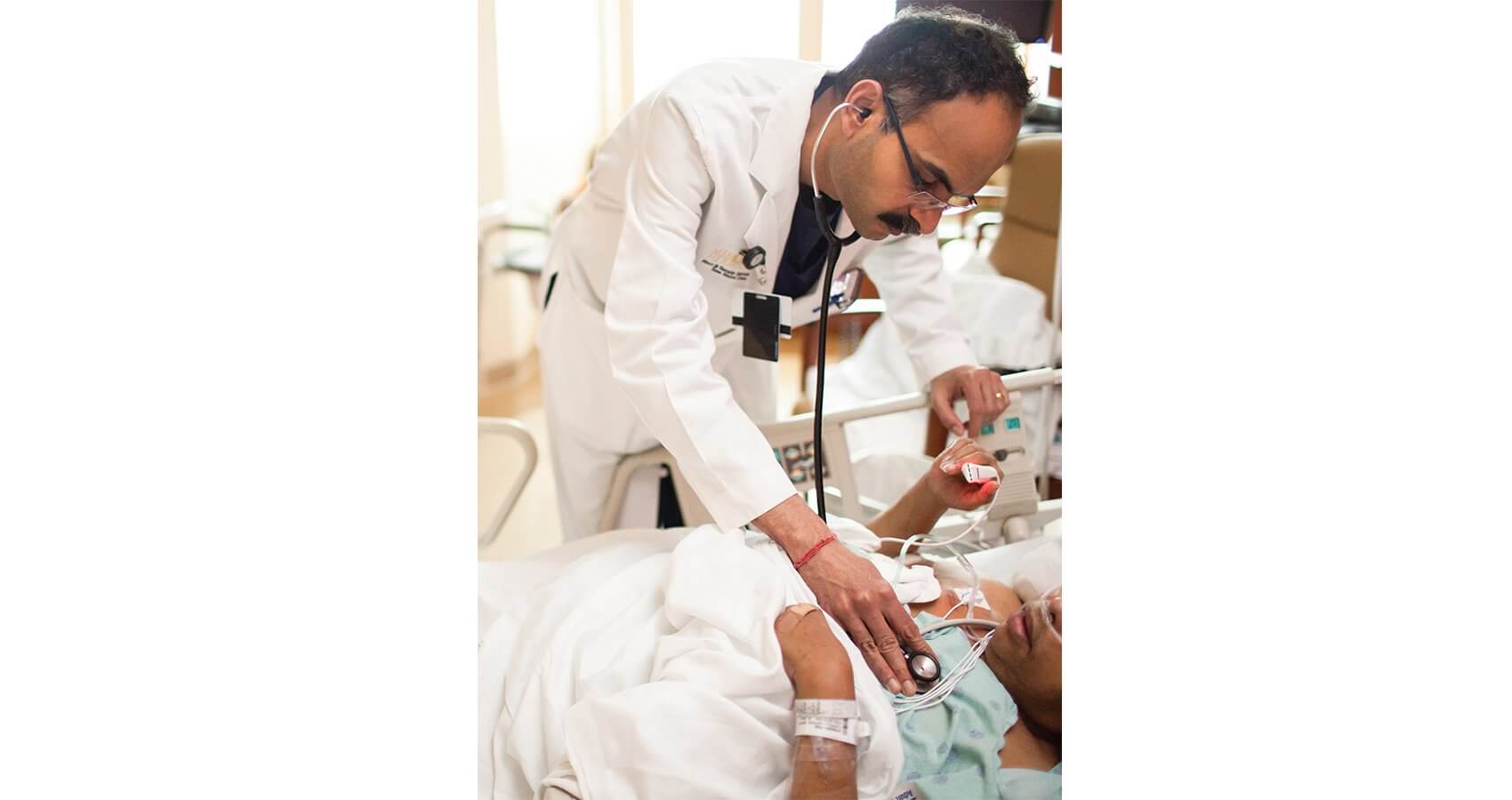

A month later, Russo met with Biswajit Kar, M.D., chief and program director of the Medical Division at the Center for Advanced Heart Failure/ UTHealth, who took an active role in her treatment every step of the way. After waiting a year, Russo was “offered the gift of a heart transplant.” She was the 19th heart transplant patient Kar treated.

For women like Diane Russo, peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM), is a life-threatening disease of the heart muscle that affects women in the last month of pregnancy and even up to five months after delivery. Although it is quite rare, no one knows for sure how many people have ever had it. Rajapreyar said it could be as low as one in 1,000.

While Russo’s case was severe and most patients recover after giving birth, symptoms of PPCM are similar to those of heart failure. Besides shortness of breath and excessive fatigue like Russo suffered, other symptoms may include rapid heartbeat or palpitations, chest pain, swelling of the feet or ankles, and tiredness during physical activity.

Sriram Nathan, M.D., director of cardiogenic shock at the Center for Advanced Heart Failure/UTHealth, who works on Kar’s research team, said the disease is more prevalent in women who are African American, middle-aged, diabetic, and those with high blood pressure.

Depending on the severity of the case, treatment varies from the use of a balloon heart pump, intravenous medication, or simply changing the diet and adding medication such as diuretics, vasodilators which dilate the blood vessels, or beta blockers, which work as blood thinners.

Rajapreyar spoke with excitement when she mentioned a breakthrough medicine called bromocriptine in South Africa. The drug works as an antagonist to prolactin, the hormone responsible for secreting breast milk.

Nathan said that a stumbling block they face is trying to keep the baby safe while treating the mother. Sometimes if the mother is far enough along in her pregnancy, they can talk about performing a C-section.

Before they could do any research on PPCM and attain any funding, Nathan said their team of medical researchers had to go before UTHealth’s Institutional Review Board, to have the legality and value of the research approved. Once they overcame that hurdle, the next one was to attain funding. Last February, through the Memorial Hermann Foundation, Memorial Hermann Heart & Vascular Institute-TMC received a grant from the Alpha Phi Foundation called Heart to Heart. In the past six months due to more funding, their research has taken off as they added a registry.

The registry works by screening obstetric patients with heart problems, such as PPCM to study biomarkers in blood samples and echocardiograms, which are then stored in a biorepository. Five years from now, researchers can then check the blood samples to help identify others with the same biomarkers. Through the registry, Nathan said doctors can determine if PPCM is exaggerated more than heart failure in the average person.

Through this process, researchers are hopeful that they will have the ability to find symptoms earlier in the pregnancy and attain a better understanding of this disease to determine who needs to be screened.

Besides helping identify the triggers of the disease along with its signs and symptoms, the registry also has the capacity to help other doctors around the world, especially in Africa, where the disease is prevalent.

“We want to ensure that this information is something other hospitals can use in the Northeast, Southwest, etc.,” said Nathan. “I generally believe this is something we should have done a long time ago.”

As to why this disease happens, Nathan has a few theories. One is a speculative connection with prolactin, the hormone responsible for secreting breast milk. Sometimes its breakdown affects the heart. Another theory is that PPCM is caused from antibodies from baby to mother whose body cannot handle them.

“We try to save the mother and the baby, but sometimes we have to tell mothers that they can’t have any more children,” said Nathan.

Russo, now a 54-year-old mother of three, takes the work Kar, Nathan, and Rajapreyar very personally. She made friends with the doctors and nurses who treated her. They and her family gave her “something to hang on to.”

They also gave her the gift of time. She will be forever grateful for the heart transplant that prolonged her life. Although she still sees a cardiologist every three months, she is happy to be able to help others, and enjoys her family and her career.

Tearing up, Russo spoke from the heart. “I am very thankful. I’ll feel indebted to these people for the rest of my life.”