The Cooley Legacy

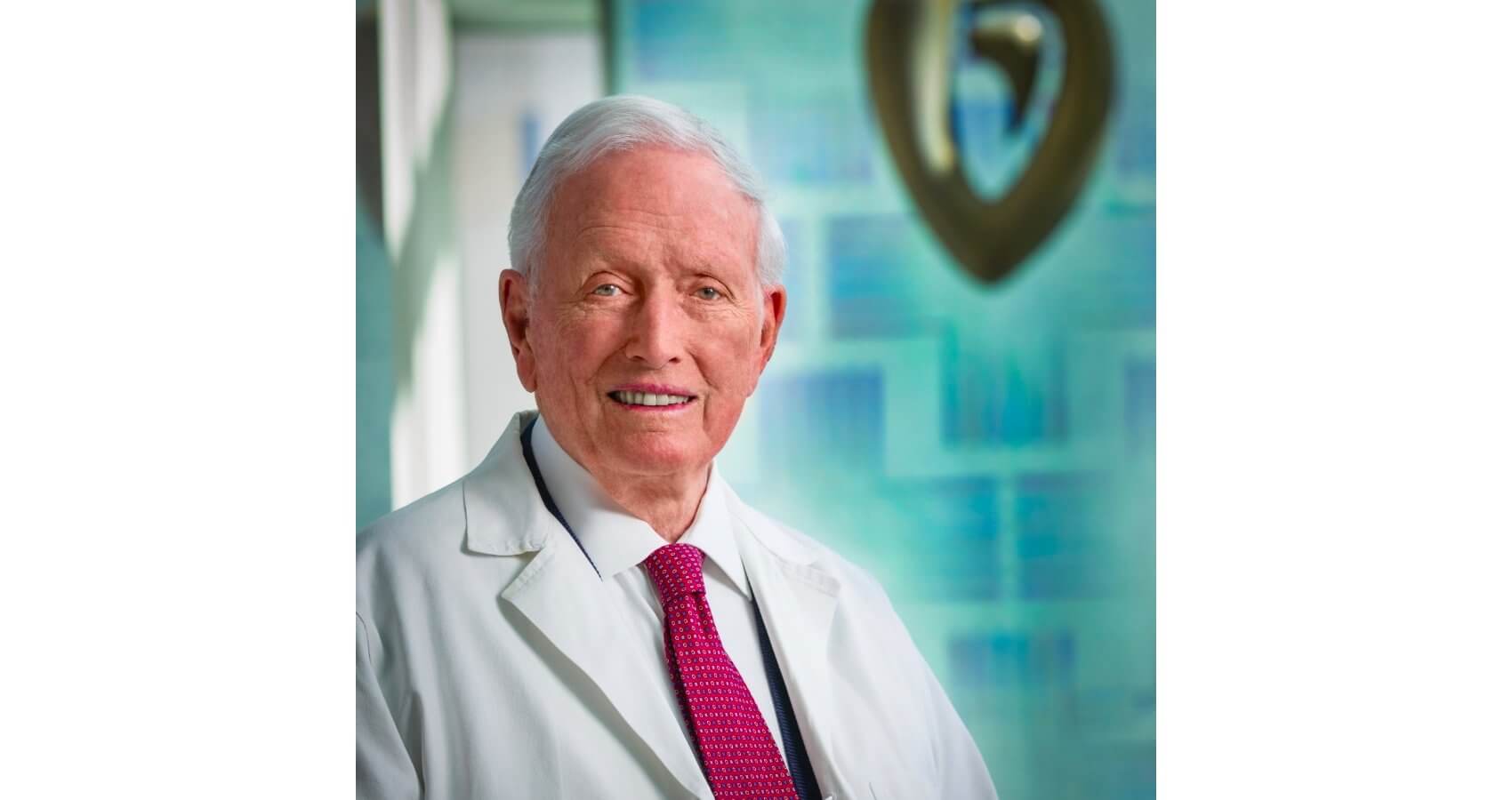

His name is almost synonymous with hearts, and his reputation as a pioneer of cardiovascular surgery is well deserved. The legacy of Denton A. Cooley, M.D., reaches far beyond the walls of the Texas Heart Institute (THI). It is alive in the patients around the world whose hearts are still beating today because of Cooley and his team.

At 94 years old, Cooley continues to work nine to five, four days a week. The way he sees it, keeping an active mind is the best way for someone his age to stay sharp. A former University of Texas varsity basketball player, Cooley graduated with highest honors from UT in 1941. He still carries a scar on his chest in the shape of a UT symbol, earned during a junior-year social club initiation ceremony by The Cowboys involving a hot branding iron and tremendous UT pride.

After two years at The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, he transferred to Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, graduating Alpha Omega Alpha in 1944. As an intern, he assisted Alfred Blalock, M.D., on the first “Blue Baby” operation. Cooley earned his medical degree from Johns Hopkins, and served as a Senior Registrar in London with Russell Brock, a prominent heart surgeon. He went on to serve as a faculty member at what is today Baylor College of Medicine alongside the late Michael E. DeBakey, M.D., then the chairman of the Baylor department of surgery. The 1950s and 60s ushered in exciting advancements in cardiovascular surgery—from the introduction of open-heart surgery, to transplantation, to mechanical assist devices—and Houston’s renowned surgeons were at the center of it.

“I did the first successful heart transplant in the United States, and I was so impressed with the fact that you could actually replace this pump for the whole circulatory system,” said Cooley. “The heart is one of the simplest organs in the body…not nearly as complex as the liver or the kidneys. The heart has only one function, which is to pump.”

The Texas Medical Center was growing at that time, and Cooley saw an opportunity to create a heart institute in a clinical partnership with what is today CHI St. Luke’s Health–Baylor St. Luke’s Medical Center.

“Dr. Cooley wanted to create an entity that would try, through research, to help people with cardiovascular disease,” said James T. Willerson, M.D., president of the Texas Heart Institute. “He and his colleagues at the time were doing most of the heart surgery for the entire United States, in adults and children. But he wanted to do more than the surgery, and he believed that he could establish a Texas Heart Institute that would be involved in research and education—the education of young doctors, in all facets of cardiovascular disease.”

Nearly seven years after the founding of the Institute, Cooley notably became the first in the world to implant a total artificial heart (TAH) in a human. The operation took place on April 4, 1969, when a device designed by Domingo Liotta, M.D., a surgical fellow at Baylor College of Medicine, was implanted as a bridge to transplant in forty-seven-year-old Haskell Karp. Karp survived the initial TAH implantation, and subsequent heart transplant sixty-four hours later, but he ultimately succumbed to renal failure and acute pneumonia.

“It was the first bridge to transplantation,” recalled Cooley. “We did not perceive having the patient live months or years with an artificial heart, we just wanted him to live long enough to find a donor.”

There have been immeasurable advances in cardiovascular medicine since then, largely due to the lessons learned from early assist and replacement devices. With each new device developed or innovative surgical procedure introduced, physicians worldwide are able to provide better patient care.

“Dr. Cooley envisioned the Texas Heart Institute as being committed to prevention and cure, as well as surgical repair,” said Willerson. “That continues still today, and all of this work needs to continue in the future. The direction is exactly the same, but continues to enhance the basic research toward curative and preventative strategies.

“It was always about building a team that would work from the subcellular up to and through the devices, as a team,” he added. “A team devoted to trying to prevent cardiovascular disease. And when we can’t prevent it, to cure it or make it much more tolerable for the individual patient.”

O.H. “Bud” Frazier, M.D., THI director of cardiovascular surgery research, and a surgeon who Cooley proudly refers to as “one of my stars,” was an early champion of mechanical circulatory support. He is known for, among many other things, being the first to implant the HeartMate I left ventricular assist device (LVAD) in a human. That device would go on to become the most widely used implantable LVAD in the world. Together with William E. Cohn, M.D., co-director of the Cullen Cardiovascular Research Laboratory at THI, Frazier remains active in the development of new heart assist and replacement devices.

The team also recently welcomed Daniel Timms, Ph.D., a biomedical engineer and native Australian who envisioned a heart replacement device that would be small enough for use in children, but powerful enough to support an active adult. He first began development of the BiVACOR total artificial heart over ten years ago as a Ph.D. candidate at Queensland University of Technology and The Prince Charles Hospital in Australia. After Timms met Cohn, Frazier and Cooley in 2012, the team began discussing plans to bring his lab to Houston. Today they continue testing on the device, hopeful that the magnetic rotating disc will reduce the likelihood of device failure due to mechanical wear over time.

Beyond mechanical devices, the THI team is also researching ways to help repair damaged hearts with the use of stem cells. Doris Taylor, Ph.D., THI director of regenerative medicine research, is exploring ways in which a patient’s heart could be repaired without the long-term use of a device. Taylor and her team have used a pig heart to demonstrate how healthy adult stem cells could potentially help repair or rebuild damaged organs.

“More women die of heart and vascular disease than all cancers combined. There are 35,000 children born each year with heart and vascular disease in the United States. And one out of 2.5 men worldwide will have heart and vascular disease during their lives,” explained Willerson. “So it’s really an important effort, and we have to help people realize that really the greatest threat to their health and their lives—no matter what their gender or age—is heart or vascular disease. And that effort has to continue.”

From treating patients to developing new surgical techniques or mechanical assist devices, the Texas Heart Institute has been impacting lives for 52 years. For those who have worked alongside Cooley in that time, credit is due, in no small part, to his personal commitment to the institute and the patients.

“Dr. Cooley is probably the very best heart surgeon who has ever lived,” said Willerson. “He has great technical skills, enormous experience, the courage to tackle these things, and wonderful judgment about what needed to be done in individual patients.

“And, of course, he is the father of the Texas Heart Institute, and certainly one of the fathers of cardiovascular surgery worldwide. He has always encouraged others to do their very best, and be the best they can be in caring for patients with cardiovascular disease.”

Though he shows no sign of slowing down any time soon, Cooley acknowledges that time with family is something he enjoys most outside of work. He and his wife Louise have been married for 68 years.

“From a personal standpoint, I have always believed that a man who is going to get ahead has to have a balanced life,” said Cooley. “I’ve tried, for most of my life, to give my first attention to my patients and to my practice, but also to my family. I have a family of women…five daughters and my wife.

“An old friend of mine just invited me to a birthday luncheon for his 100th birthday, and I told him he was sort of a role model for me. I’ve always thought life was like a marathon,” he added. “You want to save some effort for the last hundred yards and have a little kick at the finish. And that’s what I would like to do.”