Charles D. Fraser Jr., M.D.

Charles D. Fraser JR., M.D., Chief of Congenital Heart Surgery and Cardiac Surgeon-in-Charge at Texas Children’s Hospital, talks about how a background in mathematics helps him to solve challenges in surgery, and how innovation has driven fetal diagnoses today.

Q | Tell us about your early years in Midland, Texas.

A | Midland Texas was, and is, a very special and unusual place. As you know, the economy is very active out there today. I believe this is the third boom cycle that I have experienced in my life and it’s amazing to contemplate all of the opportunities I had growing up. My dad is a petroleum engineer. He and my mom moved out to Midland in about 1960, and he is still there. I think when I graduated high school there were only about 60,000 people living there, but we had extraordinary public educational opportunities. For a city its size, I believe Midland has enjoyed an usual, perhaps unique, concentration of intellectual capital and there was, to my view, a very robust public school system where we students were offered quite an advanced educational paradigm. For example, after graduating from high school, I was admitted to the University of Texas at Austin where I placed out of essentially a year and a half of courses just based on my high school preparation and advanced placement testing. This was a real advantage for me as a student.

From the standpoint of exposure to medicine, the citizens of Midland have been blessed by really outstanding doctors and a very good hospital. From early in life, I had very positive experiences with the doctors who took care of me. I had a big event when I was around 10 years old—traumatic spleen injury that required surgery—which exposed me to some really special caregivers; surgeons, pediatricians, nurses. This experience did, in a strange way, plant the seed of interest in medicine.

Q | You have a background as a mathematician. Do you think there is a correlation between mathematics and surgery?

A | I do think probably there is. People have often commented on that during the course of my career. One obvious corollary is between geometric thinking and complex reconstructive surgery. In pediatric cardiac surgery, we are often faced with the challenge of congenitally malformed hearts with complicated structures that need to be rebuilt and often reconfigured. It is an advantage, perhaps it is mandatory, for the surgeon to be able to think in a three dimension way and essentially mentally envision the reconstruction in advance of doing the actual repair. We also need to think in terms of the patient’s somatic growth and make allowances for appropriate dimensions during the course of life. From a planning perspective, I also see the development of surgical strategy as being, in many ways, mathematical. Many of our patients require multiple, complex cardiac operations over the course of life and in many instances, there are important decision points where the surgeon is faced with options that may have huge short or long term impact on the patient’s ultimate outcome. As such, a paramount issue is to be able to think critically about the possible permutations of a particular decision pathway that will have long-term consequences, both positive and negative. Unfortunately, we sometimes see patients in whom a relatively ‘easy’ short-term solution may translate into an extremely problematic long-term situation. Again, this is mathematical thinking, much as one would have to do to perform a complicated proof of a theorem, beginning with the end in mind and working through the various steps—which will not necessarily be either linear or obvious—to get to the ultimate outcome solution.

Q | Did you just have a natural affinity for medicine? What turned you in that direction?

A | I guess you never really know you have an aptitude for something until you have a chance to experience it. Some of my medical professors did comment, from very early on in medical school and then consistently throughout my residency, that I seemed to have a technical aptitude for surgery. So that always bolsters your interest and confidence when people are saying that. I hope it was true.

I went to medical school at UTMB Galveston. I decided in medical school that I wanted to be a children’s surgeon. In fact, I didn’t really like surgeons all that much in medical school. They seemed to me to be a bit misbehaved— always gruff and pretty unhappy and unpleasant. So I had this perception that maybe that was necessary, particularly in cardiac surgery. If you were going to be a successful surgeon, you would have to be pretty rough. So I went to Johns Hopkins as a subintern, pretty well intent on not being a cardiac surgeon, but having more interest in pediatric surgery. I was lucky enough to get a match for residency there in general pediatric surgery.

I can remember the day Bruce Reitz and Bill Baumgartner walked in. They are nice guys, gentlemen and brilliant surgeons. Certainly you would never say they were anything but courageous as surgeons, but they did it in a way that was very appealing to me. So we just got along really well. And as you might expect, they surrounded themselves with tremendous people at Hopkins. So Bruce came to me after I did my cardiac rotation as an intern and said, ‘Look, don’t cut off your nose to spite your face. You seem to have an aptitude for this. Why don’t you come and join us on the cardiac service side?’ So I changed from pediatric surgery to heart surgery.

Children are so amazing in the sense of how well they tolerate surgery and how quickly they recover. I can remember an epiphanous case that really opened my eyes to the notion of being a children’s surgeon. It was a child who had a gunshot wound. At that time, at UTMB, we took care of the whole of the state, because every child that came from a county that didn’t have a county hospital came to UTMB for care. So we had a huge children’s hospital there. Now they don’t, unfortunately. But this little girl was from somewhere up in North Texas, and she had a terrible gunshot wound to the buttocks. And I remember wondering how she would ever possibly recover from that horrible injury. And I’ll be darned if she didn’t just heal. It was just remarkable how well she healed. And I remember thinking that this was almost miraculous.

So I started learning about the physiology of children, and this notion that you could do these operations that would transform lives for decades was very appealing to me. And also just the way that the children respond to treatment. If you walk through our cardiac ICU, it is just remarkable how the kids just do things that we can’t do as adults. They respond, they get better and off they go. So it is very gratifying. And I just started to see that fit with my personality. You see a problem, you fix it, you see an immediate result. And I kind of liked that connection to therapy.

Q | Looking at innovation, what are some things that you are doing today that you couldn’t have done five years ago?

A | Well, we are almost uniformly making fetal diagnoses for all newborns. It is an aberration to have a newborn who comes to us and is diagnosed postnatal. I just operated yesterday on a child who was a postnatal diagnosis, and we were all shocked. And this child came through a sophisticated health care system.

The imaging has just gotten better and better, and the knowledge has gotten better. So that has allowed us to move into the realm of fetal planning. Fetal intervention is still pretty much experimental in the cardiac world, but definitely fetal planning, that’s part of our norm now. We start seeing these children early in gestation, we meet the families, we plan for delivery, and we discuss contingencies. That’s a big change in the last five to ten years. It’s sort of a standard of practice now for newborn management, and it has, of course, allowed us the proposition of fetal intervention.

Q | What are the cases that you find the most satisfying?

A | Well, I tend to be referred a lot of challenging cases. That’s been my reputation of late. I just came down from the clinic, seeing a child who’s got a lot of complicated problems, cardiac and non-cardiac. So, to me, that’s intriguing, because every child that comes through that referral network, we have to do a lot of head-scratching. Each one is different from the last one. And in some of them, no one has seen cases like theirs before. We had one just this week, no one had ever seen it, no one had ever heard of it. And that’s quite amazing.

Q | What do you do with that kind of case, when there is no precedence from which to work?

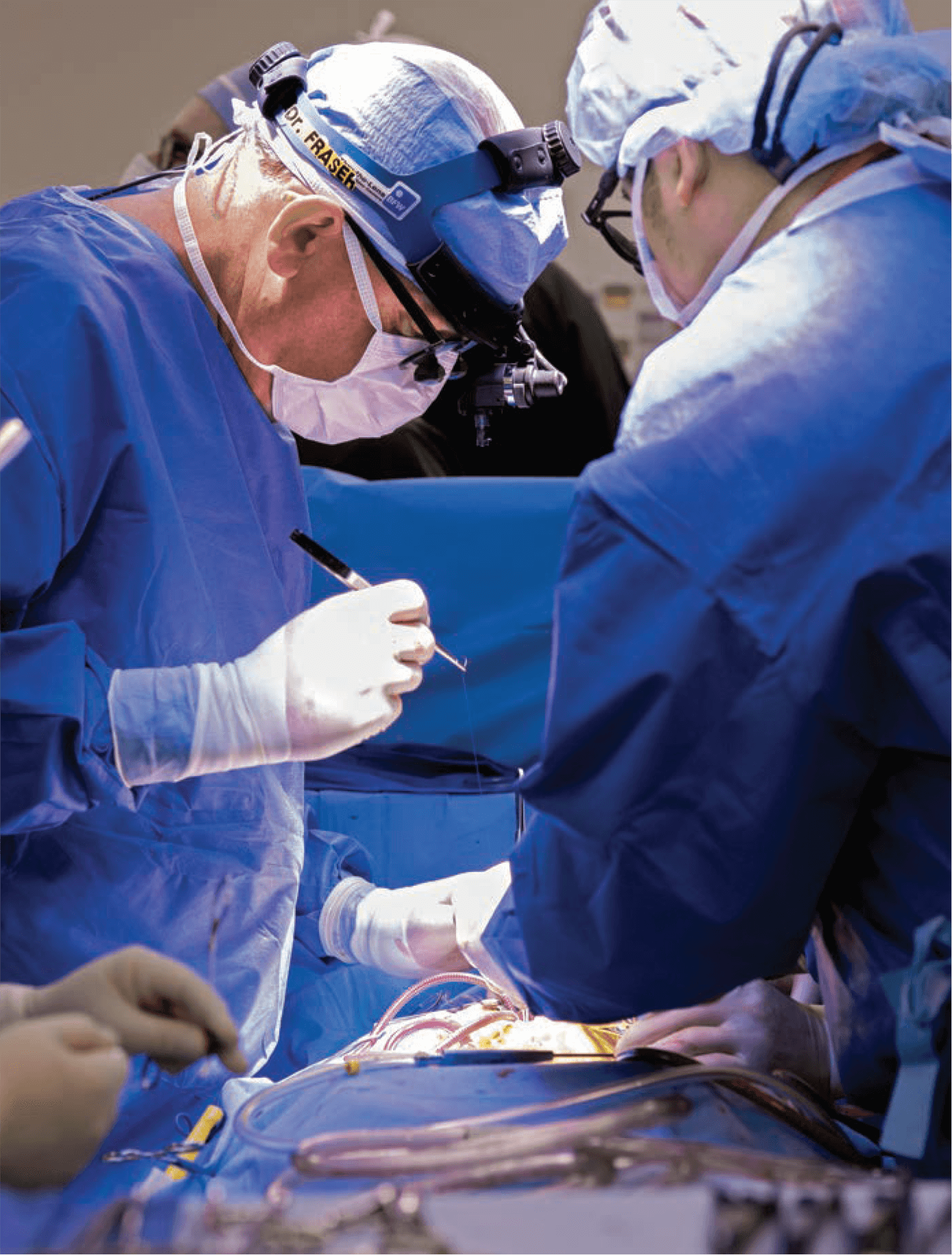

A | Well, that’s the great thing about being in our field. I think you do have to innovate and improvise a lot. That can be from a technological standpoint, applying something that you didn’t apply to that before. And then, even in the categorical conditions where you think it would become more boilerplate, there are always nuances in difference with anatomy, presentation and physiology. But as far as operations, my signature operation is probably the arterial switch operation. I’ve just done lots of them, and had a really good track record.

Q | Tell us about some of your mentors.

A | I can go way back. In high school, I had some great teachers, great educators. I had a great doctor in Midland, who I was very close to. I had a traumatic spleen injury when I was about ten, so I had to have an operation and spent a lot of time in the hospital, and that actually changed my life. Because I couldn’t play sports that summer, I ended up doing other things. And then in the fall, my dad didn’t want me playing football, so I started playing tennis, and I became a tennis player. We actually lived right across the street from tennis courts, so I started hanging out over there and playing tennis. So that really changed the trajectory of my athletic life. Then I became very close to the doctor when I was sick, so he kind of mentored me through childhood.

And then I had an amazing experience in medical school. I had a couple of doctors who were very influential. But at that time, UTMB had, and still does I think, between your first and second year, you have two months off. It’s the only time you have off in medial school there. And they really encouraged the students to go out and do something practical. They had an office that would assign you places. So I got assigned to a hospital out in Andrews, Texas, which is far West Texas. It was a very unusual community, probably five or six thousand people, one hospital…I think we had two operating rooms, probably the whole hospital was 50 beds. It had an emergency department. I lived in the hospital, and worked for a general surgeon who was the most amazing man. And we did everything. We operated, we delivered babies, we took care of rattlesnake bites, we did breast augmentations, we did hysterectomies, we did children’s surgeries, we went all over West Texas and did emergencies. It was unbelievable. I think about that experience as a rising second year student, and the things I got to see and do. And this guy was very important to me from the ministry of medicine, and the way he went about it.

And then, you know, as I went along, residency, there were others that really influenced me. And then, I had a rotation in Australia, which was an extraordinary experience. The principle surgeon there was a guy named Roger Mee, and he really changed my professional life as a pediatric heart surgeon. He was the guy who really taught me how to do it.

Q | What do you look forward to most about the future?

A | I do think that there are going to be incremental breakthroughs in technology. I’m not personally betting on a mechanical solution for circulatory problems in childhood, because we have the problem of somatic growth. And I could be wrong about that, because when these pumps get more and more miniaturized, there is more opportunity for broader application.

But you know how children fiddle with things, and being tethered to a machine is also problematic. So I’m still holding on to the biologic solution, and bioengineering, and tissue regeneration. And we have developed and maintained an interest and collaborations. There is enormous unrealized collective potential here, and of course, collaboratively across the world. But that’s where I see some striking opportunities on the horizon. A tissue engineered heart valve for children would be transformative.

I think that on the scientific side of things, I see the next decade in pediatric surgery linked with tissue regeneration and some forms of cell therapy for surgical problems. But frankly, I think the bigger incremental upside is in the organization of care. I really do. I don’t think that patients get the right care out in the world.

We do so much remedial surgery here. I would say that half of the surgery that we do is remediation. There is not broad knowledge. Of course, my field is super specialized, but there are a lot of super specialized enterprises in places like Texas Children’s in cancer, in neuroscience. And I think that we can continue to push the world of structural integration, of outcomes, measurement, and the right care at the right place at the right time. And in medicine, we are still very disjointed.

To toot the horn of Texas Children’s a bit, I think that’s an opportunity we have through our integrated delivery system. This system of pediatric practices, our relationships now, extend across the state and hopefully eventually across the world. Where we communicated effectively electronically, we have giant data repositories. We have a group of people that work on outcomes analysis. There are extraordinary things that we have been able to do and learn in the last few years. And for simple problems like appendectomies, we have been able to reduce the length of stay for appendectomies for this organization exponentially, just by looking at the way that antibiotics are administered, and the timing of antibiotics, and diagnostic assessment. And I see that, again, if outlook at the scope of influence, much bigger than building a heart valve. A heart valve is really cool, and it is going to really help, but when you think about the coordination of care, I’m betting on that.

Q | What are you most proud of when you look back on your career to date?

A | That’s an easy one. From a professional standpoint, I’m most proud of all of the people that I get to associate with here every day. I said, almost as soon as I got here, that I wanted to build a program that was the same when I’m here as when I’m not here. A program that I would bring my children to. And that’s what we have. This place never closes.

I work with four surgeons who are the most extraordinary surgeons anywhere. They are just brilliant technical surgeons, brilliant thinkers, and great people on top of that. And it just goes on and on. We have fantastic colleagues in anesthesia, in cardiology, in critical care, our administrative team, our nursing team, our research team, and I look back, and none of it was here. So I am proud of the community that we have built. And I can’t say that I built it, I just helped catalyze it in some ways. But it keeps growing. So that is enormously gratifying. It also keeps me coming back. There is something exciting going on every day.

Q | How do you describe the Texas Medical Center to people who have not been here?

A | With great challenge. I’ll try not to be too trite about this, but I think the Texas Medical Center is Texas. Texas is a place that if you are from Texas, you are very proud of this side of things. If you are not from Texas, it can be thought of somewhat disparagingly. But it can be this unbelievable sea of opportunity. And that’s the Texas Medical Center. It’s just this swirling mass of opportunity.

We don’t always get it all right. I think Dr. Robbins would be the first to say there are some redundancies here that probably shouldn’t be. On the other hand, there are things that have happened here that probably wouldn’t have happened any other place, and some of it probably has come from the redundancies and the internal horserace. It’s just an energized place. It’s pulsing all of the time. You can just feel it when you come here.

And when I am trying to convince people to move here, that’s kind of what I try to tell them. It’s why I came here, frankly. There’s just an opportunity replete environment here. If you are ambitious, and energized, you can do things here that you are probably not going to be able to do anywhere else, or certainly not at the pace that we do.